Policy Background

In 2017, 1,147 people were killed by the police,[1] and in the 100 largest cities between 2013 and 2017, Black people comprised 39 percent of those killed despite comprising only 21 percent of the population.[2] Police in the United States kill more people per day than other countries do in years.[3] For example, in the course of a decade (between 2003 and 2013), British police fired their weapons a total of 51 times.[4]

Despite the pervasive use of force employed by police departments across the country, there is no national standard governing use-of-force policies,[5] which leads to significant subjectivity when prosecuting officers for excessive use of force.[6] Further, use of force in many states violates international standards, which dictate that police should use deadly force only as a last resort. U.S. state laws allow police to use deadly force in a much broader range of circumstances.[7]

To achieve greater accountability, local elected officials can play an important role in advocating for strong use-of-force policies that prioritize the sanctity of life, put limits on the type of force officers can use and under what circumstances, and require robust data collection and reporting.

Assessing the Landscape

Additional questions to help assess the current landscape include:

- What is state law governing use of force?

- Is local law enforcement’s use-of-force policy more robust than what is required undertate law?

- What kind of data reporting policies are in place, and what kind of oversight structures exist to ensure accountability?

Best Practices

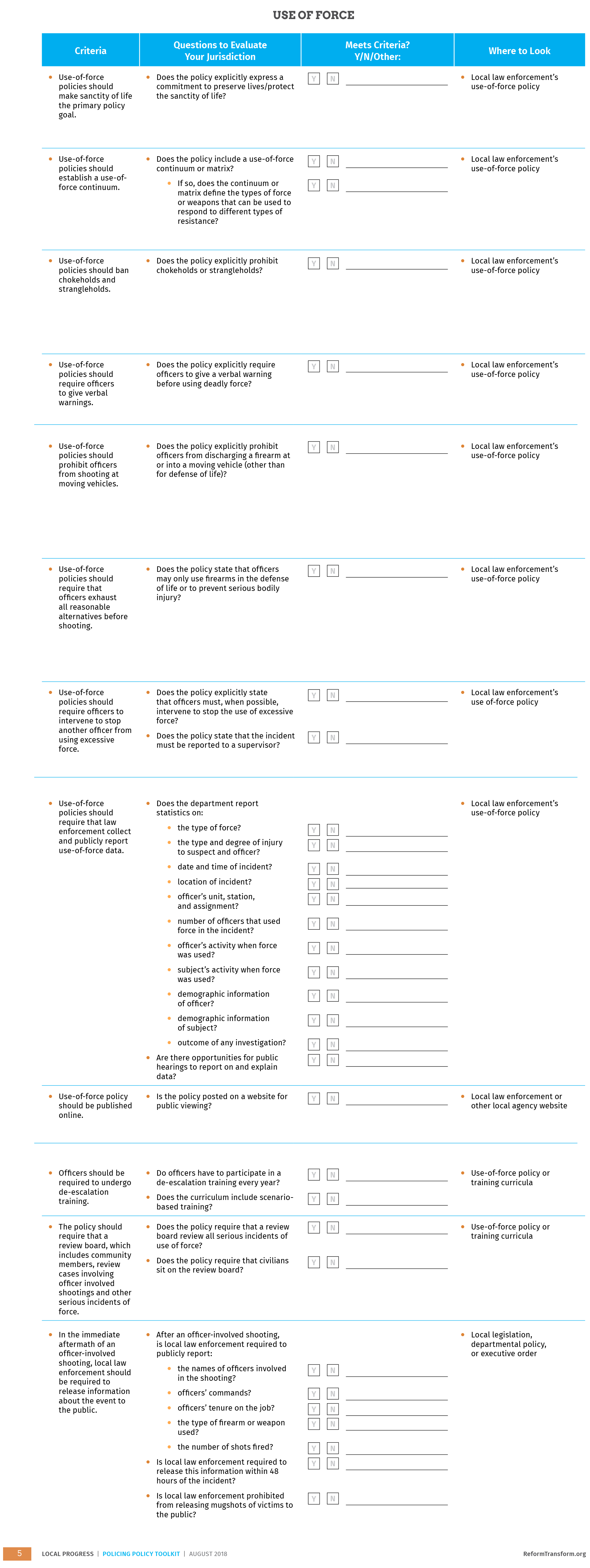

Depending on particular legal and statutory limitations, local elected officials may not be able to directly legislate the content of a use-of-force policy. But they should be able to pass legislation mandating that local law enforcement develop a strong use-of-force policy, make the policy public, and collect and report on data. Robust use-of-force policies should consider the following criteria, derived primarily from Campaign Zero’s Police Use of Force Project and model legislation[8] as well as conversations with policy experts at the Legal Defense Fund. Criteria about de-escalation training is drawn from U.S. Representative (WI-04) Gwen Moore’s bill, H.R. 3060.[9]

Additional Considerations

- Officers should have to undergo regular training on topics such as police bias, procedural justice, and fairness in policing that are designed to minimize the use of excessive force.

- If the law enforcement is empowered to determine the final language in the use-of-force policy, there should be democratic input from a variety of sources, including research organizations and community groups.

Lessons from the Field

Berkeley, CA

Councilmember Kate Harrison

In late 2017, Councilmember Kate Harrison and her colleagues on the Berkeley City Council proposed a number of reforms to the Berkeley Police Department’s use-of-force policy, among other items. The reform on use of force expands the department’s definition to include any confrontation where physical force is used and would require a report to be submitted in each such instance. Currently, officers are only required to file reports when injuries occur, when a weapon is used, or when a citizen files a complaint. The council’s reforms also include more robust reporting requirements so that officers themselves have to write incident reports: every officer involved in the incident would have to contribute to the reporting, as opposed to commanders writing reports for officers. Finally, the reforms would increase transparency by ensuring that data is reported in a digital format to make it accessible to the public. The Berkeley Police Department began work on the reforms in February 2018.

These Berkeley City Council recommendations were issued after a confluence of events going back to December 2014. At the time, there were a number of Black Lives Matter gatherings in the city where several people were injured by the police. Although the police department was required to file a report after the injuries occurred, the council did not receive a report until many months later. Some of those injured sued the department and won, affirming that the department had problems when it came to interactions with protestors. Later, at a council debate over withdrawing from federally funded national-security programs, police again clashed with demonstrators. And in the spring and summer of 2017, alt-right rallies led to numerous injuries and arrests of those protesting their presence. These high-profile events led the Berkeley Police Department to ask the UCLA’s Center for Policing Equity to analyze the police department’s data on use of force (as well as stops, citations, and searches). The findings revealed significant disparities in use of force applied toward Black residents; Blacks were 12 times more likely to experience use of force by the police than whites. Additionally, as Berkeley’s Police Review Commission (PRC) began to analyze police department data, it realized that the data portal was difficult to navigate and poorly organized, creating a lack of transparency and accountability.

In developing these reforms, the council worked closely with the NAACP, the ACLU, Cop Watch, the Oakland Privacy Network, and leading police reform experts. The council also drew from the experiences of police departments in neighboring jurisdictions such as Oakland and Bay Area Rapid Transit. These departments had recently experienced scandals and were forced to reform their use-of-force policies as a result.

The biggest obstacle that Councilmember Harrison and her colleagues faced was an absence of recognition of how poor police-community relationships can impact departments—even those like Berkeley’s, which is generally better regarded than departments in other jurisdictions (for example, in Ferguson, MO).The council argued that, because of inadequate data collection and reporting practices, the city did not actually have complete and accurate data to assess the extent of the problem. Notably, the council pointed out that reporting was only required after major incidents of use of force and that this did not reflect the many instances of lower-level use-of-force activity not receiving adequate attention.

Most recently, in addition to her leadership in issuing these use of force recommendations, Councilmember Harrison spearheaded a recommendation to create a task force charged with addressing the racial disparities that were revealed through the PRC and UCLA analysis of use-of-force data. In April 2018, the council voted unanimously to create this task force.

San Francisco, CA

John Avalos, former Supervisor

As San Francisco Supervisor, John Avalos leveraged his budget oversight to pressure the San Francisco Police Department to reform use-of-force practices. Because the Board of Supervisors faced challenges to enacting legislation to curb the use of force, Avalos found creative ways to assert influence through the city budget itself. Instead of rubber stamping every request for new equipment, Avalos exhorted his colleagues to scrutinize every request for new equipment, from radios and surveillance equipment to use-of-force equipment like service weapons and conductive devices (otherwise known as tasers). As a budget committee member in 2012, he held public hearings opposing tasers as well as the arming of youth probation officers with service weapons. Due to his efforts, the city ended up saving hundreds of thousands of dollars in unnecessary spending.

In 2016, after a series of high profile and controversial killings of Black and Brown residents by police officers, the U.S. Department of Justice recommended a number of reforms that the San Francisco Police Department was mandated to enact. Supervisor Avalos attempted to pass legislation that would place a significant portion of the police budget on reserve so that it would only be released once the department demonstrated progress toward the reforms. Although the policy did not pass, this model legislation could potentially be useful for local elected officials in other jurisdictions. For more information on former Supervisor Avalos’ budget advocacy, see “Investments in Public Safety Beyond Policing” in this toolkit.

Resources

- See Campaign Zero’s Police Use of Force Policy Analysis, which assess 91 of the largest 100 police departments in the United States: http://useofforceproject.org/#review

- See Campaign Zero’s Model Use of Force Policy: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56996151cbced68b170389f4/t/5defffb38594a9745b936b64/1576009651688/Campaign+Zero+Model+Use+of+Force+Policy.pdf

- See the PolicyLink and Advancement Project report “Limiting Use of Force: Promising Community-Centered Strategies”, http://www.policylink.org/sites/default/files/pl_police_use%20of%20force_111914_a.pdf

- See “Mapping Police Violence,” for up-to-date statistics on incidents of use of force nationwide: https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/

- See if your local law enforcement agency is a participant in the Police Data Initiative, launched under the Obama administration: https://www.policedatainitiative.org/

- See the Police Executive Research Forum’s report, “Guiding Principles on Use of Force: http://www.policeforum.org/assets/guidingprinciples1.pdf

- See Wisconsin Congresswoman Gwen Moore’s bill (H.R. 3060) on de-escalation training: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/115/hr3060/text