Policy Background

Bans on bias-based policing prohibit officers from targeting individuals based on their perceived race, socioeconomic status, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, immigration status, language, disability status, or housing status. There is no evidence that bias-based policing is an effective law enforcement strategy that leads to greater public safety.[1] In fact, statistics show that profiling is ineffective—just 0.1 percent of the New York Police Department’s (NYPD) racially biased stop-question-and-frisk stops resulted in a conviction for a violent crime or possession, according to a 2013 report released by the New York Attorney General.[2] Instead, bias-based policing breeds mistrust of law enforcement by impacted community members.[3]

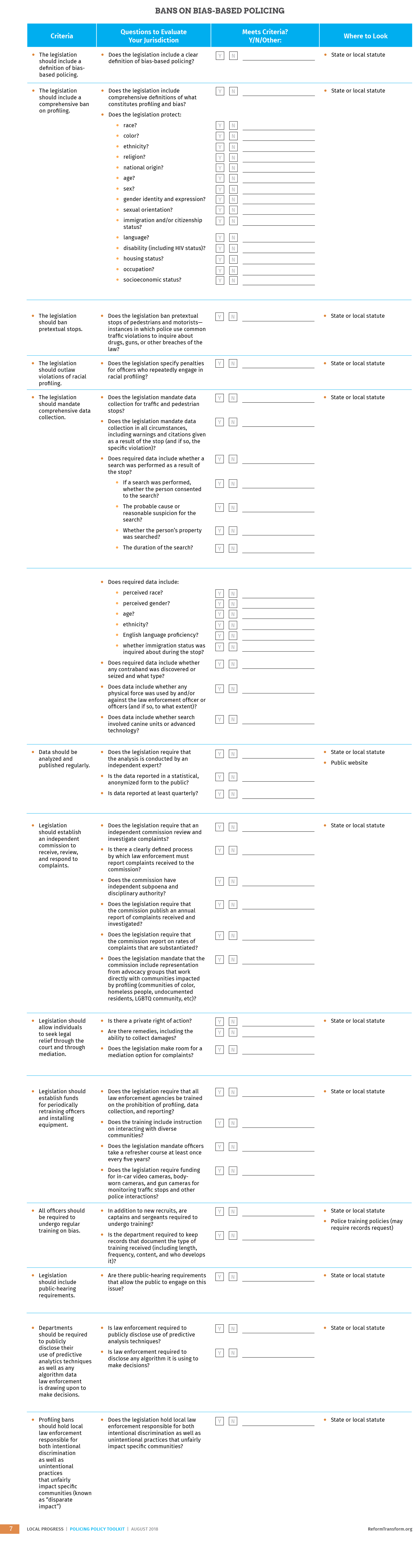

For a ban on bias-based policing to be effective, it should include a comprehensive definition of protected categories and robust measures for data collection and reporting, mandate disciplinary measures that are enforceable in court for officers that violate the law, and require recurring training for officers. However, a ban on the books only solves one part of the problem; there must also be measures in place for dealing with bias-based policing when it does occur, such as strong mechanisms for independent intake, investigation, and reporting on complaints, as well as a private right of action.

Assessing the Landscape

The following questions can help to provide additional local context:

- Does state legislation ban profiling?

- Is there additional legislation at the local level banning profiling or increasing data collection and transparency?

- What kind of oversight structures exist to ensure accountability?

Best Practices

Though bans on profiling are often established through state law, local elected officials often have authority to pass stronger local legislation to curb racial profiling or increase data collection and transparency. There should be more aggressive oversight by local elected officials when constitutional rights are at stake. The following criteria for effective state or local legislation to ban profiling and other forms of bias-based policing are derived from the NAACP’s model bill and criteria[4] as well as conversations with policy experts.

Additional Considerations

- When settlements are paid out, funds should come from law enforcement budgets and not from the general fund.

- Jurisdictions should also consider reforms to end surveillance and racially biased investigator practices:

- Civilian monitors should have strong oversight over intelligence gathering and surveillance.

- Investigations in which race, religion, or ethnicity is a substantial or motivating factor should be prohibited.

- Officers should have to account for the potential effect of investigative techniques on constitutionally protected activities such as religious worship and political meetings.

- Police should be required to produce factual information before launching an investigation into political or religious activity.

- The use of undercovers and confidential informants to situations should be limited.[5]

Lessons from the Field

Council Member Jumaane Williams

Ending Bias-Based Policing

In 2013, New York City Council Member Jumaane Williams and his colleagues, working with allies across the city, passed the Community Safety Act (CSA), a landmark legislative package that included legislation to effectively prohibit bias-based policing.[6] Advocates seeking to address a number of abuses in policing, including stop-question-and-frisk, had approached city council with a package of bills to enact reform within the NYPD. Although New York City had already banned bias-based policing, the ban had not been enforceable. In order to give the policy teeth, the new legislation included a private right of action. It also expanded protected categories beyond race and ethnicity to include sexual orientation, gender identity, citizenship status, and housing status. The same year, the council passed legislation that would establish an inspector general to oversee and audit the NYPD’s policies and practices.[7]

Leading up to 2013, the political climate was ripe for police accountability reform. Stop-question-and-frisk usage was at an all-time high. Data showed that in recent years, the NYPD had stopped more young Black men than the total number of Black men living in the New York City—meaning that individual Black men were being stopped multiple times by the police. It was important for advocates to be able to show the police the department’s own data in making the case for reform. Then Council Member Williams was himself profiled and arrested at the 2011 West Indian Day Parade alongside his friend and fellow activist Minister Kirsten John Foy. Even after Williams identified himself to the police as a council member, he was cuffed and briefly detained, only to be released with no charges.[8] The high-profile arrest of Williams created a groundswell of mobilization by advocates and provided an opportunity to more widely communicate the dire need for reform.

The campaign was fueled by a broad, diverse coalition of advocates, including organizations that represented Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ community members. It also included members of the Muslim community who had specific experiences of being surveilled and targeted by the NYPD. This coalition played a crucial role in the passage of the reform because its members had been directly impacted by the policing policies and practices that so badly needed reform. Williams said it was “the best inside/outside strategy [he’d] ever been a part of.”

Council Member Williams and his colleagues faced opposition by the former mayor and the police union. To counter this opposition, Williams grounded his argument in data and worked to humanize the issue. He took care not to villainize the opposition and made the argument that the reform would ultimately help the police do their job more effectively. In the end, the council secured and maintained the 34 votes needed to override the mayor’s veto. When the legislation was later challenged by the police union, the State Supreme Court Justice upheld the law, protecting the right to sue as a means of ensuring consequences to using profiling to make stops.[9]

Ending Discriminatory Surveillance Practices

In 2011, at the same time that there was a groundswell of organizing to end stop-question-and-frisk in New York City, the NYPD came under fire for its use of racially biased surveillance of Muslim communities. A 2011 Associated Press investigative probe found that the NYPD had mapped Muslim communities and their religious, educational, social, and business institutions, and they had secretly dispatched undercover officers into communities without any suspicion of wrongdoing.[10] In this moment of heightened awareness around the need for police reform, American Muslim advocates and community organizations alike came together to formulate a coordinated response, much of which was done under a newly formed coalition, the Muslim American Civil Liberties Coalition (MACLC). MACLC and its component organizations ensured that surveillance became an integral issue within the police accountability conversation, and that Muslim communities also showed up for other communities impacted by other discriminatory policing practices. As a result, an unprecedented alliance of advocates banded together in New York City to form a coalition that included American Muslim groups and other community groups of color with a longer history of organizing around police accountability.

The coalition took a multi-pronged approach in their advocacy. An important part of the effort was to bring community experiences and perspectives to the table in order to concretely show that NYPD surveillance practices were damaging and harmful. To this end, MACLC, the Creating Law Enforcement Accountability & Responsibility (CLEAR) project, and the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) produced a groundbreaking report, “Mapping Muslims: NYPD Spying and its Impact on American Muslims,” which highlighted, through interviews and stories, the ways that surveillance of Muslims creates a pervasive climate of fear.[11] Advocates used this report in city council hearings to keep the issue on the agenda and generate continued attention around the issue. And advocates in the New York Muslim community fought alongside other allies towards the passage of the Community Safety Act, which instituted protections and oversight to curb racially biased surveillance practices.[12] These efforts forced many decision-makers to disavow past surveillance practices,[13] creating a wedge issue for the mayoral election.

On a parallel track, advocates challenged the legality of surveillance practices. In 2013, the American Civil Liberties Union, New York Civil Liberties Union, and the CLEAR project filed a lawsuit asserting that the NYPD’s surveillance program violated constitutional rights to equal protection and free exercise of religious beliefs. A settlement was finalized in 2017, which jointly addressed the 2013 lawsuit (the Raza case) as well as a long-standing class action lawsuit that challenged the NYPD’s surveillance of political groups and activists (the Handschu case).[14] The settlement established a number of reforms that were designed to prevent the use of discriminatory surveillance practices (see, “Additional Considerations,” above).[15] In New Jersey, the Center for Constitutional Rights and Muslim advocates also sued the NYPD; the case, Hassan v. City of New York, also settled in 2018.

Resources

- See New York City’s legislation to end the use of bias-based policing: http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=1444267&GUID=BCB20F20-50EF-4E9B-8919-C51E15182DBF&Options=ID|Text|&Search=1080

- See the New York City Administrative Code, § 14-151, for an example of a clear definition of bias-based policing: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/cchr/downloads/pdf/human-rights/030414_biasbased_profiling.pdf

- See legislation establishing the New York City’s Inspector General: http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/oignypd/downloads/pdf/Local-Law-70.pdf

- See a New York City bill that would require reporting and oversight of surveillance technologies: http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=3343878&GUID=996ABB2A-9F4C-4A32-B081-D6F24AB954A0&Options=&Search=

- See the NAACP’s report, “Born Suspect: Stop-and-Frisk Abuses & the Continued Fight to End Racial Profiling in America,” which includes a model bill (Appendix III): http://action.naacp.org/page/-/Criminal%20Justice/Born_Suspect_Report_final_web.pdf

- See the Vera Institute’s study, “Coming of Age with Stop and Frisk”: https://www.vera.org/projects/stop-question-and-frisk-study

- See the Muslim American Civil Liberties Coalition (MACLC), the Creating Law Enforcement Accountability and Responsibility (CLEAR) project, and the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) report, “Mapping Muslims: NYPD Spying and its Impact on American Muslims”: http://www.law.cuny.edu/academics/clinics/immigration/clear/Mapping-Muslims.pdf