Policy Background

An over-reliance on incarceration, coupled with a failure to adequately invest in the resources and supports that truly keep communities safe, has meant that millions of people are funneled through the penal system while their underlying needs go unaddressed. For example, of the 2.3 million people who are incarcerated at the federal, state, and local levels, half a million are locked up because of a drug offense.[1] Additionally, approximately 20 percent of those in jails and 15 percent of those in state prisons have a serious mental illness.[2]

Instead of subjecting people who need special treatment or services to harsh punishments through the penal system, diversion programs enable local law enforcement to identify these individuals and direct them to appropriate channels for support. Diversion is both sensible and effective. It reduces recidivism, saves costs associated with the criminal legal system (for example, expenditures on attorneys and incarceration), and improves housing and employment outcomes for participants.[3]

While some diversion programs serve as interventions at the point of arraignment, pre-booking diversion programs enable local law enforcement to intercede before involving the courts, saving significant time and resources, and sparing people the trauma of arrest and forcible detention. For example, the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) model is a pre-booking diversion model that bypasses the costs and time associated with booking, charging, and requiring court appearances.[4] New York City has a pre-arrest diversion program for homeless individuals seeking shelter in trains and subways in which individuals are directed to health and housing services instead of being arrested.[5] These types of pre-arrest and pre-booking programs are also sometimes referred to as deflection programs, which are distinct from diversion programs that are operated pre-trial in order to divert people from prison. For example, drug court is a court-based diversion program that offers people who are arrested and prosecuted a non-incarceratory sentence, such as community treatment and ongoing court supervision.

Assessing the Landscape

The following considerations may help as a starting point when contemplating a diversion program:

- Who are the treatment and service providers that should be engaged in a diversion program?

- Who are the peer outreach groups that should be engaged in a diversion program?

- What is law enforcement’s self-interest in a diversion program? How does the program offer law enforcement a better alternative than the current system?

- What are the low-level offenses that lead to high volumes of arrests?

- What penal offenses are city-based, and what could be converted to ticketable offenses? It can be helpful to understand this landscape in order to identify the types of service interventions that would serve as a good starting place for a diversion program.

- What are the demographics of those individuals being arrested for low-level offenses (historically and presently), and are there identifiable racial biases?

Best Practices

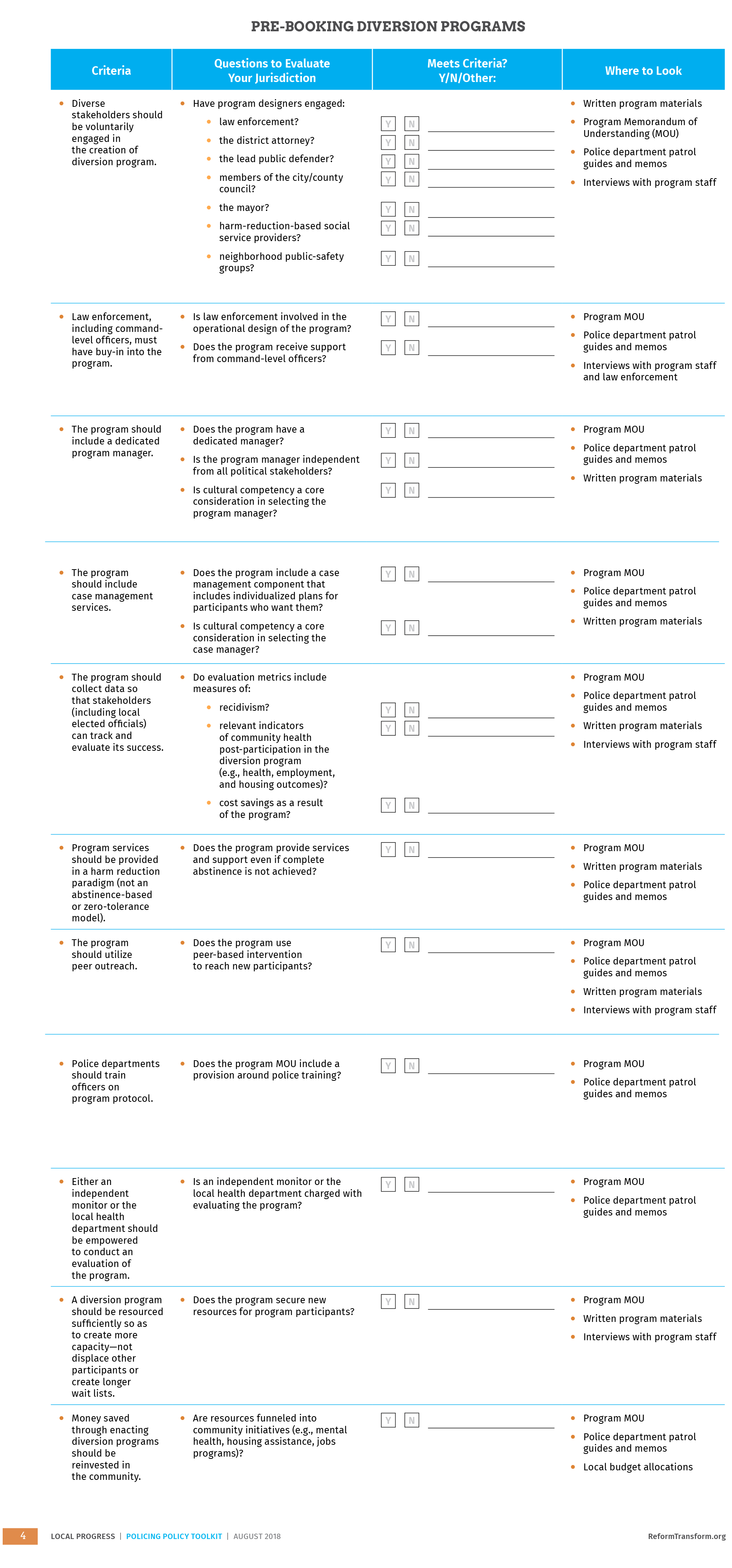

Because written rules will limit the ability for case-by-case discretion, advocates strongly advise that legislators do not adopt legislation around the programming of diversion initiatives. Instead, local elected officials can play an important role in securing permanent funding, facilitating partnerships between community organizations and the locality to assist with programmatic needs, and periodically conducting evaluations. Below are a number of considerations for stakeholders when contemplating program design, derived from the Center for Popular Democracy and PolicyLink’s Justice in Policing Toolkit[6] and LEAD principles[7] and informed by conversations with policy experts at the Public Defender Association, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and the Center for Court Innovation.

Lessons from the Field

Councilmember Lorena Gonzalez

Since 1998, the Public Defender Association (PDA) in Seattle/King County has housed the Racial Disparity Project (RDP), which works to reduce racial disparities within the criminal legal system.[8] In its early years, RDP had a concentrated focus on drug enforcement and litigated a high-profile challenge to racial disparity in Seattle drug arrests. After several rounds of litigation, the King County Prosecutor reached out to RDP to propose that they work together to develop a new policy direction. Through conversations with clients and community members, they developed a strong sense that the city should not narrowly focus on reducing harmful enforcement practices, but should champion an alternative that included real investment in and support for people.

The outcome was the establishment of LEAD, giving law enforcement officers the ability to redirect people who have committed low-level offences like drug or prostitution activity to community-based services.[9] Launched in 2011, the initiative is a partnership between Seattle’s PDA, the Seattle Police Department, the King County Sheriff, the King County Prosecutor, the Seattle City Attorney, the Seattle Mayor’s Office, the King County Executive, the Seattle City Council, the King County Council, the ACLU-WA, and a number of neighborhood and public safety leaders.[10] The PDA serves as Project Manager for the program, and also is a partner of the LEAD National Support Bureau, which supports other jurisdictions in developing other models based on LEAD principles.[11]

When Councilmember Lorena Gonzalez took office in 2015, LEAD was already a successful program, receiving buy-in from community advocates, law enforcement, and city officials. However the program was still in its pilot phase and advocates were pushing for public funding through the city budget. Largely due to advocacy from community groups as well as the timely release of a positive program evaluation, Councilmember Gonzalez and her colleagues succeeded in securing taxpayer dollars for the program. Since then, the city council has engaged in annual budget advocacy to increase allocations for LEAD so that the initiative can expand to other parts of the city. In her budget advocacy, Gonzalez understood it was crucial that her colleagues understood not just the emotional value of the initiative but the necessity of ongoing monetary investment.

Even as LEAD enjoyed broad popularity with the general public, Councilmember Gonzalez found it challenging to make the case for the expansion of LEAD funding given the multiple competing priorities within the city budget. So she and her colleagues worked closely with advocates to craft a compelling narrative about LEAD, highlighting its important role in addressing homelessness and drug addiction. A second challenge was that many elected officials wanted to see LEAD scaled up immediately, but advocates were concerned that rapid growth could compromise the effectiveness of the program. Ultimately, councilmembers relied on the deep knowledge and experience of advocates and organizations representing impacted communities and kept the program at current scale to ensure its ongoing success.

In addition to her budget advocacy, Councilmember Gonzalez has played an important role in ensuring the thoughtful implementation of LEAD. For example, she continues to work closely with advocates and impacted communities because their participation is critical to translating the spirit of LEAD into concrete outcomes. She also worked to make sure that community-based organizations—who were already on the ground, serving impacted communities—were compensated for their collaboration in the program. Finally, Gonzalez and her staff have paid close and crucial attention to the racial impact of the program to ensure that communities of color, who are disproportionately targeted through policing, benefit from LEAD.

Resources

- See information about King County’s LEAD program model: http://leadkingcounty.org

- See the MOU establishing the King County LEAD program: https://www.scribd.com/doc/267032932/Seattle-Diversion-Program-MOU

- See the LEAD National Support Bureau’s core principles: https://www.leadbureau.org/resources

- Read about the human impact of LEAD: https://www.deseretnews.com/article/900006079/police-found-her-in-a-parking-garage-with-a-crack-pipe-what-they-did-next-will-surprise-you.html

- Watch a video about the impact of the LEAD: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fiCgqtbu2ks

- See information about New York City’s pre-arrest diversion program for homeless individuals: https://www.jjay.cuny.edu/pre-arrest-diversion-homeless-individuals

- See information on the Center for Court Innovation’s Project Reset, a pre-arraignment diversion program for youth: https://www.courtinnovation.org/programs/project-reset