Policy Background

The school-to-prison-and-deportation pipeline is one of the most egregious manifestations of systemic racism, violence, and inequality in our country. The permanent presence of police officers, guns, and metal detectors at schools attended by mostly Black and Brown youth, together with harsh, punitive, and exclusionary discipline policies, create hostile teaching and learning environments.

This practice of invading schools with police began in earnest during the 1940s and 1950s as a reaction to schools desegregating.[1] Since then, the rate of police presence in schools has ballooned. In 1975, merely one percent of schools had police.[2] By 2004, 36 percent of schools reported having police.[3] In 2017, 42 percent of high schools had police.[4] The National Association of School Resource Officers estimates that between 14,000 and 20,000 school resource officers are in service nationwide.[5] In New York City alone, there are 5,511 school safety agents patrolling schools.[6]

This drastic expansion was, in part, spurred by reaction to the Columbine shooting. During this time, federal, state and local programs emerged to infuse more than a million dollars into criminalizing schools.[7] These programs led to more policing and a deep infrastructure of criminalization; “[f]or example, nationwide increases in school security and police presence in the wake of the Columbine tragedy…led to increased use of metal detectors, surveillance cameras, pat-downs, drug-sniffing dogs, and tasers.”[8]

The country is currently experiencing another spike in school policing. After the Parkland shooting, some elected officials and policymakers doubled-down on the worst policies and practices carried out in the name of school safety. The National Conference of State Legislatures noted that, by April 2018, over 200 bills or resolutions dealing with school safety had been passed in 39 different states—with more than half introduced after the Parkland school shooting.[9] Forty-four of those bills (in 20 different states) included measures to arm school personnel, while 12 state legislatures introduced bills mandating the presence of school resource officers at K–12 schools.[10]

Rather than promoting school safety, these measures will instead re-entrench the school-to-prison-and-deportation pipeline and directly undermine school safety, particularly for youth of color. Police are disproportionately concentrated in communities of color, with 51 percent of high schools with majority Black and Latinx students having officers on campus.[11] Research shows Black and Latinx students do not misbehave more frequently or in a more severe manner than white students, yet they are disproportionately arrested and referred to court.[12] Across the country, Black students are more than twice as likely to be referred to the police or arrested in school than their white peers.[13] In some places the disparity is particularly pronounced. For example, in New York City, Black girls are nearly 13 times more likely to be arrested and nearly 7 times more likely to be issued a summons than their white peers.[14]

These punitive practices have devastating impacts. One study found that experiencing an arrest for the first time in high school nearly doubles the odds of the student dropping out, and a court appearance nearly quadruples the odds of the student dropping out.[15] Police interactions also cause lasting psychological harm. Recent research shows that, over time, the mere presence of police may have a compounding psychological effect on students’ “nervous and immune systems that may result in anxiety, restlessness, lack of motivation, inability to focus, social withdrawal, and aggressive behaviors.”[16] Students often see officers’ presence as regulating them rather than protecting them. In fact, several studies have shown that police presence makes students feel less safe than if there were no police in the school.[17]

Proponents of school policing often cite student safety as their primary justification. Yet there is no substantial evidentiary support for the proposition that police presence in schools create safer learning environments.[18] In fact, studies have shown that even after years of punitive policing and disciplinary measures, schools are no safer than before such policies are implemented.[19] Rather than reduce school violence, the presence of police merely criminalizes typical adolescent behavior, such as disorderly conduct, even among similarly situated schools.[20] The same is true for surveillance measures: After reviewing several empirical studies examining the effectiveness of metal detectors, researchers found that there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate that metal detectors reduce school violence.[21]

As advocates have pointed out, problems like these cannot be solved by regulating police or by increasing police training.[22] The root cause of the problem is policing itself because police involvement “in school discipline … disrupts the learning environment by diminishing students’ belief in the legitimacy of school staff authority and by creating an adversarial relationship between school officials and students.”[23] The solution is to remove regular police presence and surveillance equipment, such as metal detectors, from schools.

The school-to-prison-and-deportation pipeline is not only a grave violation of fundamental human rights and freedoms and ineffective and counterintuitive to promotion of school safety, but it is also a costly drain on public funds. Indeed, “[e]very dollar that goes into police, metal detectors, and surveillance cameras is a dollar that could have been used for teachers, guidance counselors, school psychologists.”[24]

Assessing the Landscape

Additional questions to assess the current landscape include:

- How much money is spent to uphold the criminalization of schools through policing and security infrastructure? How does this compare to support services, such as funding for guidance counselors or mental health care? When possible, compare this funding over time.

- Which agency has control over police and/or security in schools? It is under the department of education, police department, independent agency, another formation, or some combination of these options?

- What is the size of the police or security force in and around schools?

- If data is available, how often do police arrest, ticket, or otherwise intervene in schools?

Best Practices

Cities and counties should remove police officers and so-called security infrastructure (e.g. metal detectors, all weapons) from schools. The money that currently supports the criminalization of schools should be divested from those programs and instead invested in teachers, restorative practices, guidance counselors, mental health care, and other programs that young people demand.

During the process of removing police from schools, their presence on campuses should be closely monitored through data collection and restrictions on how they interact with young people.

Local elected officials can influence school policing by revoking the funding, or portions of the funding, for this program. In addition, local elected officials can enact data and transparency laws about the use of police and criminalization infrastructure in schools. Finally, local elected officials can also play an important oversight and advocacy role by calling for oversight hearings about this issue or by requiring the police and education departments to develop policies about police presence in schools. The substance of those policies may be at the discretion of the departments.

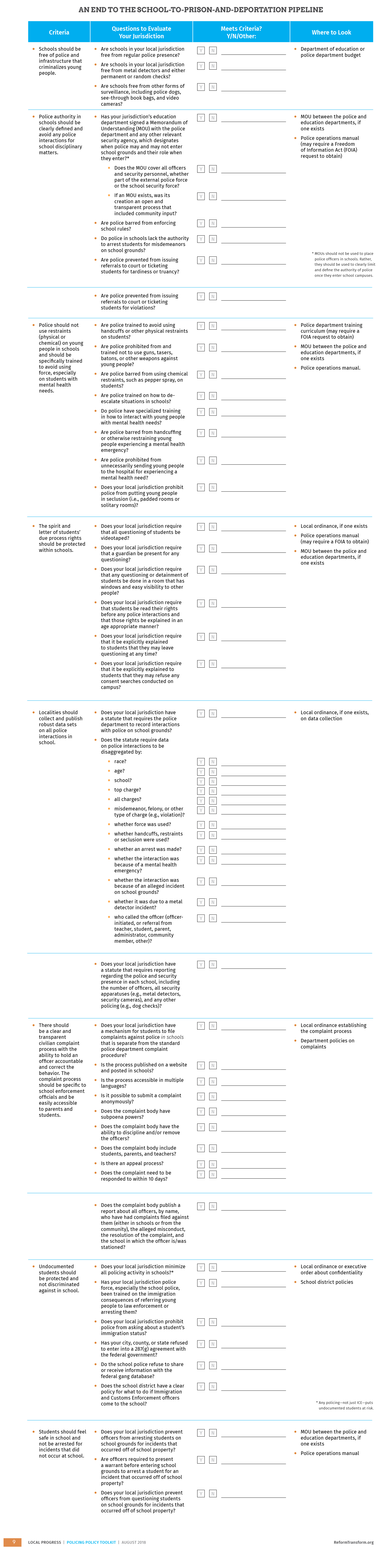

The Center for Popular Democracy and Local Progress developed the following criteria based on our work with the Urban Youth Collaborative in New York City, Leaders Igniting Transformation in Milwaukee, and other partnerships. The criteria were also informed by conversations with the Advancement Project.

Lessons from the Field

Council Member Antonio Reynoso

While serving on the education committee in 2015, New York City Council Member Antonio Reynoso fought alongside advocates to secure $2.4 million in funding for restorative justice—a school-wide approach to ending discriminatory disciplinary practices, and which instead focuses on “building safe and supportive school communities that [focus] on repairing harm, rebuilding relationships, and collectively holding students and adults accountable for their actions.”[25]

To achieve this victory, the campaign—led by young organizers and leaders organizing with Urban Youth Collaborative and operating with the support of allies in council—first had to demonstrate to both the city council and the general public that the fight for restorative justice was fundamentally about addressing discrimination and racial bias. To make the case, the campaign leveraged available data to show that the students who were being disciplined were overwhelmingly Black, Brown and low-income. Once the campaign was able to build a narrative about the racially biased nature of discipline and then advance this narrative through the media, they successfully gained broader support from the public, additional council colleagues, and the mayor. Importantly, the campaign won the support of parents by making the case that disciplinary practices were ultimately hurting students’ ability to learn.

Yet, while the data was compelling, it was not robust enough to demonstrate the full extent of racial discrimination in schools. For example, the Department of Education (DOE) was tracking suspensions, but not disaggregating data by race. To address this data gap, Council Member Reynoso introduced a reporting bill that required the DOE to track the demographics of students, including race and gender.[26] He also introduced a bill that required the DOE to track the number of guidance counselors in schools,[27] which brought to light the disproportionate number of officers in schools compared to counselors. This data revealed that principals were spending money on tutors to help students catch up, leaving minimal funding for counselors. As a result, schools were primarily dealing with behavioral and emotional issues through school suspensions. Because of these findings, there is now a minimum number of counselors that schools are required to employ, funded separately from the principal’s bottom line.

There was also the challenge of pushing for real impact. While many city officials were on board with the idea of restorative justice broadly, their proposals were not bold enough in the eyes of many young people. For example, the DOE chancellor expressed support for restorative justice, but did not share advocates’ goals of eliminating all officers and metal detectors in schools or ceasing all suspensions. Robust outside organizing was crucial to pushing for a more progressive agenda, and young people led the way. The Urban Youth Collaborative—comprised almost exclusively of young people—showed up at hearings to tell their personal stories of unjust suspensions and discipline. Reynoso and his colleagues on the education committee made sure that young people were the first to speak at hearings, which forced the DOE to respond directly to them. Young people attended every rally and were well-prepared to make the argument about the importance of restorative justice. They were also backed by effective community organizations and unions that could lend their institutional power to the fight.

Today, due to the successful organizing of community organizations and the leadership of young people, funding for restorative justice is now baselined into the New York City budget.

Resources

- See an analysis of police in schools by the Advancement Project, Dignity in Schools Campaign, Alliance for Educational Justice, and NAACP Legal Defense Fund, “Police in Schools is Not the Answer to School Shootings” (Re-released March 2018): https://advancementproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Police-In-Schools-2018-FINAL.pdf

- See policy recommendations to end the regular presence of law enforcement in schools from the Dignity in Schools Campaign: https://dignityinsc.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/DSC_Counselors_Not_Cops_Recommendations-1.pdf

- See a School-to-Deportation action toolkit developed by the Advancement Project: https://advancementproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/School-to-Deportation-Pipeline-Action-Kit-FINAL-compressed.pdf

- See policy reforms from cities across the country collected by the ACLU of Pennsylvania at EndZeroTolerance.org: http://www.endzerotolerance.org/police-in-schools-policy-reforms

- See New York City’s data reporting law on school discipline, Local Law 93: http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=2253272&GUID=9BACC627-DB3A-455C-861E-9CE4C35AFAAC