Policy Background

Over the last several years, jurisdictions that limit the extent to which local government (and especially local police) will help facilitate the deportation of non-citizens have come to be known as “sanctuary cities.” The term refers to the centuries-old religious practice of sanctuary, whereby a faith community shields a person from unjust arrest or punishment by ruling authorities. It includes the offer of physical refuge within the community’s church, temple, or other sacred space. Throughout history, sanctuary has been an act of resistance against systemic injustice, a form of civil disobedience that involves the moral imperative to give cover to those targeted by unjust laws by standing with them. In the 1980s, the sanctuary movement, a network of U.S.-based faith groups, offered support and protection to Central American refugees fleeing violence in their home countries—violence that stemmed from U.S.-funded civil conflict in the region.[1]

Today there are over 300 jurisdictions—including cities, counties, and several states—that restrict cooperation with immigration enforcement to some extent. The vast majority of these restrictions aim to stop the co-optation of local law enforcement. Over the last decade, the federal government has increasingly come to rely on local criminal justice systems as force multipliers to carry out immigration enforcement operations. These actions can include sending Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers into local jails to search for people to deport, deputizing police officers to act as ICE officers, requesting that local jails hold people on ICE’s behalf or notify ICE of a person’s release, contracting with local jails for detention bed space, targeting individuals with past criminal convictions for deportation, and requesting or compelling local governments to share confidential information about local residents.[2] Cities and counties can resist these tactics through a variety of laws and policies limiting the extent to which local resources, ostensibly devoted to public safety and crime prevention, can be diverted to support enforcement of civil immigration laws.

The intertwining of the federal immigration system with local criminal justice systems is problematic in several ways. First, it erodes trust of law enforcement within immigrant communities.[3] Immigrants are less likely to report a crime, cooperate with police investigations, or seek help from the police if there is a risk that they or their loved ones may be reported to ICE. In fact, a recent study found that localities with sanctuary policies are safer than those without such policies.[4] Second, combining immigration enforcement with local law enforcement compounds injustices within both systems. Immigrants are often first pulled into the local criminal justice system through racial profiling by police, which, in turn, enables the immigration system to target them for deportation. Intensifying the injustice even further, immigrants must then navigate an immigration system that lacks even the most basic due-process protections.

Assessing the Landscape

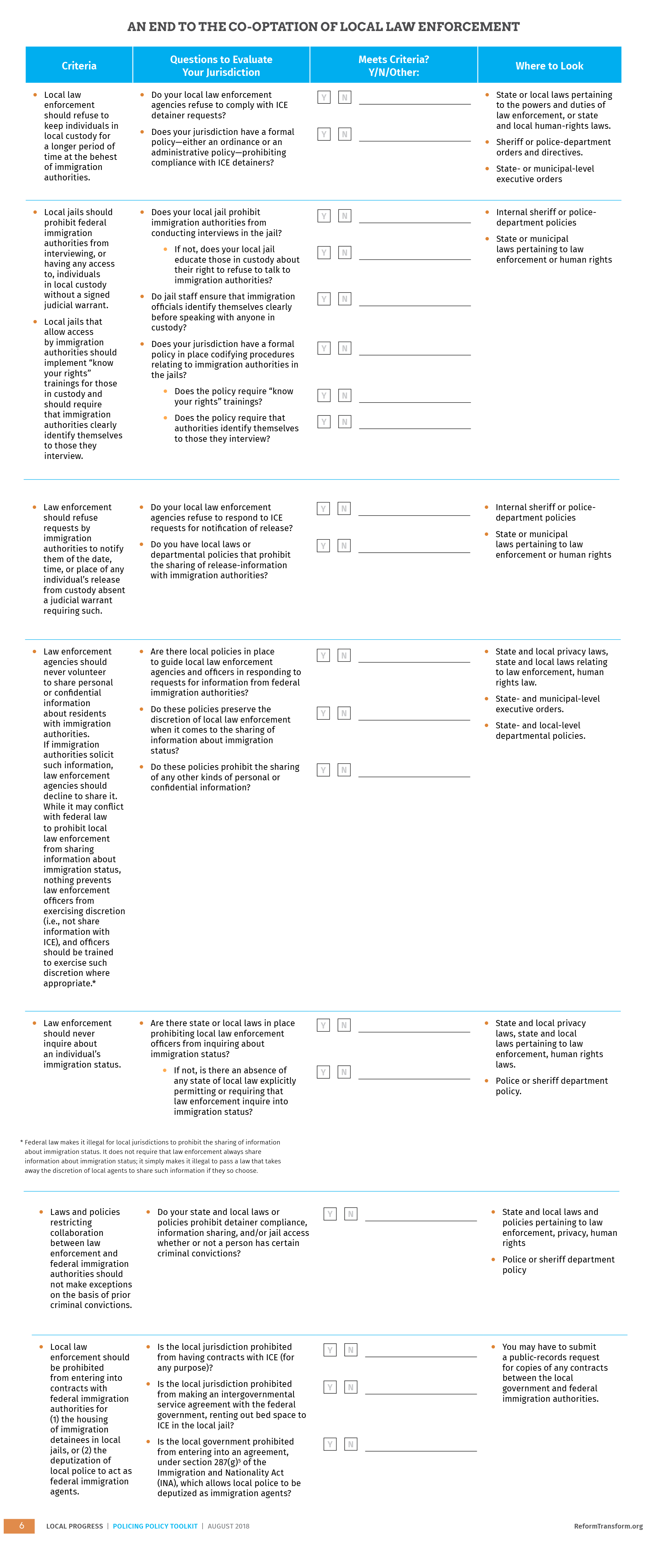

Identifying and assessing local law enforcement’s involvement in immigration enforcement can be complicated because it implicates so many different areas of law and policy, at so many different levels of government. The following questions will help to identify the prevailing practices in the area, as well as the levers of power that are most relevant to the particular way that immigration enforcement is happening locally. Some of the most crucial questions include:

- Which law enforcement entity has the most interaction with the immigrant community? (In some places this may be the city police department; in other places it is the county sheriff’s department.)

- Which agency, or agencies, receive detainer requests from ICE?

- How do local law enforcement agencies respond to federal immigration authorities’ requests to hold someone in custody or share information about them?

- Does the local legislative authority have oversight over the law enforcement entity having the most interaction with immigration authorities?

- Is there an existing state-law framework that constrains what local jurisdictions can do to limit cooperation with federal immigration authorities?

Best Practices

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), through its subsidiary agencies ICE and Customs and Border Patrol (CBP), interposes its deportation agenda at several different points within local criminal justice systems. Cities should enact policies that are comprehensive and designed to resist each aspect of federal co-optation.

An ideal sanctuary city policy will prohibit:

- holding any person in custody solely on the basis of an ICE detainer or ICE administrative warrant;

- sharing information about a person’s jail release date with DHS;

- sharing other personal non-public information about an individual with DHS;

- inquiring into or gathering information about an individual’s immigration status;

- arresting any individual on the basis of immigration-related information contained in the National Crime Information Center database;

- allowing DHS access to jail facilities, or to persons in local custody, for the purpose of investigating violations of federal immigration law;

and include the following:

- a provision terminating any existing contracts with DHS to house individuals in local jails and prohibiting any such contracts going forward;

- a provision prohibiting the deputizing of police to act as DHS agents, terminating any existing such agreements between the local jurisdiction and DHS, and prohibiting the creation of any new such agreements in the future (known as 287g agreements);

- the requirement that prosecutors consider immigration consequences in deciding whether to bring and how to resolve criminal cases in their jurisdiction; and

- a mechanism for oversight and enforcement of all aspects of the policy. To this end the policy should be codified in law as an ordinance voted upon by the legislative body of the city or county in question.

One strategy that some jurisdictions have used for covering many of these policy points without having to enumerate them is to pass an ordinance prohibiting the expenditure of any local resources on the enforcement of immigration law. These laws mean that no local dollars, staff time, or facilities can be used to help carry out deportations. Cook County, IL, Santa Clara, CA, and New York City have local laws of this type.

It is helpful to remember that, as important as immigrant-specific protections are, any reforms designed to improve accountability of law enforcement to communities of color will have a positive impact on immigrant communities. Reforms that work to reduce bias-based policing, for example, will help limit the number of interactions that immigrants are having with police, which will lead to fewer arrests, and which will ultimately mean that fewer people coming come to the attention of ICE. Other key reforms that will have a significant impact on the deportation pipeline include pre-arrest diversion programs and the decriminalization of low-level offenses.

Lessons from the Field

County Supervisor Dave Cortese

Long before anti-immigrant rhetoric became the norm under the Trump administration, Santa Clara County took a bold step in leadership in an effort to reduce the interaction between their local police force and ICE. In 2011, following a 3-2 vote, County Supervisor Dave Cortese ushered in a new policy to protect immigrants, which limited the scope under which the county would honor ICE requests to hold inmates following their release.

John Pedigo, a Catholic priest, was one of the first Santa Clara leaders to begin organizing around this issue because his church was in a predominantly immigrant community and several members of the congregation talked about family members being detained in confession. Working in partnership with community groups, including People Acting in Community Together (PACT), Justice for Immigrants (JFI) and others, the Santa Clara Board of Supervisors decided they needed to address ongoing concerns about their detainer policy.

As the board soon discovered, the sheriff was holding people in local jails for multiple federal agencies. Although it was unclear for whom they were being held, the board soon learned through the chief of corrections that the Sheriff’s department was willingly complying with ICE requests. The board also learned that they had 399 people detained, and only 26 of them had a “dangerous background” while the rest were held for minor infractions and misdemeanors. It appeared that the 399 people had Latinx surnames and some had been held for more than 180 days. Not only did the board feel compelled to address this as a moral issue, but it was also evident that, as ICE officers shirked responsibility by ensuring their asks were “voluntary,” the county faced a serious risk of lawsuits regarding due process and other civil rights issues.

Because Cook County, IL, had already passed a similar bill limiting collaboration with ICE, County Supervisor Cortese felt that precedent meant they were in strong legal standing to pass their own legislation. Unsurprisingly, the board faced opposition from the district attorney and the county sheriff. But in the days before the vote, the chief county counsel advised the board that a detained inmate could file a lawsuit against the county if it continued to detain people for ICE.

In the seven years since the narrow vote limiting cooperation with ICE, Santa Clara County has not changed its protective policy, despite an attempt to do so by the county’s district attorney. Instead, the Trump administration’s radical escalation of the attacks on sanctuary cities has solidified the county’s confidence in the necessity of their policy. In the face of Trump’s threats, Santa Clara has been leading on national lawsuits that have resulted in a permanent injunction protecting cities and counties across the United States from the President’s Executive Order of January 25, 2017.

Resources

- See the Center for Popular Democracy’s Sanctuary City Toolkit: https://populardemocracy.org/news/publications/protecting-immigrant-communities-municipal-policy-confront-mass-deportation-and

- See the Immigrant Legal Resource Center’s Immigration Enforcement Map: https://www.ilrc.org/local-enforcement-map

- See Cook County’s Sanctuary Ordinance: https://immigrantjustice.org/sites/default/files/Cook%20County%20Detainer%20Ordinance%20(enacted).pdf

- See the New York City Law Prohibiting Expenditure of Local Resources on Immigration Enforcement (Attachment 13): http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=3022098&GUID=D0BFA473-FA7C-4FA6-83C4-216E9706EE7A

- See Seattle’s Welcoming Cities Resolution: http://www.seattle.gov/council/issues/welcoming-cities-resolution

- See the Santa Clara County Sanctuary Ordinance: https://www.ilrc.org/sites/default/files/resources/santa_clara_ordinance.pdf