Policy Background

When stopped by the police, people are constitutionally protected from unreasonable or unjustified searches and have the right to deny requests to be searched if officers lack legal cause. In reality, many people who are stopped by officers are never asked for consent and are unaware that they have the right to refuse a search. Additionally, people often do not know why they are being stopped, and because of an inherent power imbalance between officers and civilians, they are too afraid to ask and risk retaliation.[1] Police-identification and consent-to-search legislation, sometimes referred to as “right to know” legislation, can mitigate the potential for abuse by ensuring that civilians provide voluntary consent to searches and decline consent when there is no legal justification.[2]

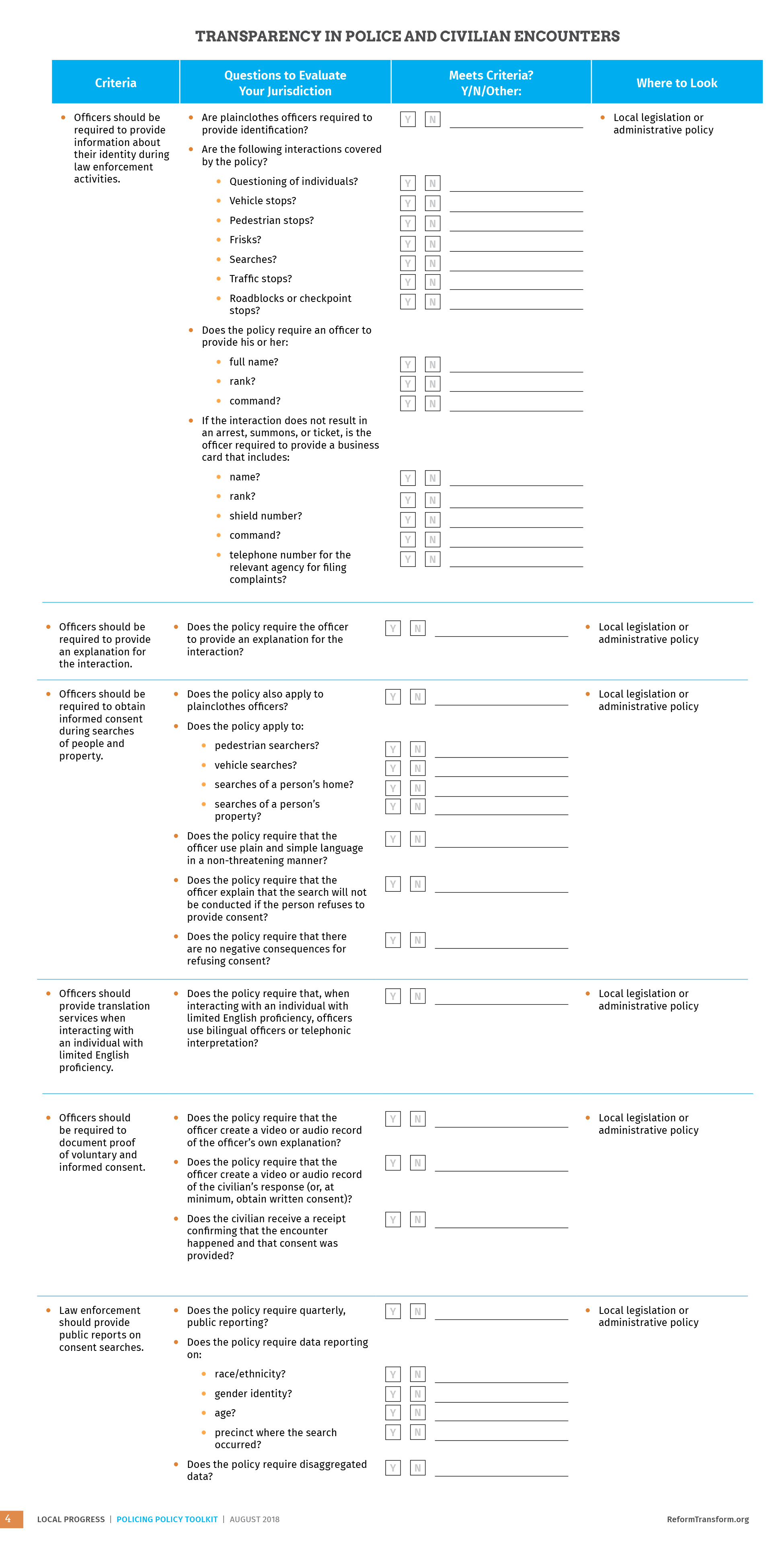

Police-identification legislation should require that officers identify themselves to the public by providing information such as the officer’s name, rank, and command during all interactions and stops. Police-identification legislation should also require that officers provide a specific legal justification for a stop. Consent-to-search legislation should require that officers explain to civilians that they have the right to refuse a search where there is no legal justification, and obtain proof that informed and voluntary consent was provided.

Assessing the Landscape

The following questions can help to provide additional local context:

- What police departmental policies currently exist regarding transparency between civilian and police interactions?

- Are there departmental policies that can be strengthened and enforced legislatively?

Best Practices

Local elected officials can pass police-identification and consent-to-search legislation to ensure greater transparency and equity in police and civilian interactions. Even when internal departmental policy exists, local legislation can help to ensure compliance and accountability. The following recommendations are drawn from model legislation by Communities United for Police Reform (CPR)[3] and New York City’s Right to Know Legislation.[4]

Lessons from the Field

Council Member Dorcey Applyrs

In 2017, Council Member Dorcey Applyrs championed and passed a police-identification law through Albany, New York’s Common Council, which requires police officers to provide a business card, including information about the officer and contact information for the Citizens’ Police Review Board (CPRB).[5]

Against a national backdrop in which the general public was paying increased attention to issues of police accountability, and following an incident in Albany where an unarmed Black man with mental health needs was tased and killed while in police custody, Council Member Applyrs saw an opportunity to advance police reform in Albany. In response to these moments of crisis and trauma, Applyrs and several of her colleagues participated in a community meeting to assess how they could address police violence. Out of this initial gathering, a diverse coalition comprised of community groups, the faith community, and elected officials quickly formed. Key members of the group included representation from the Albany Community Police Advisory Committee, the Center for Law and Justice, local churches, and TruHeart Inc., a local non-profit organization. The coalition began as a broad criminal justice and policing reform group that facilitated ongoing community events and conversations. For example, the group organized an event at a local church with a focus on healing through the arts in an effort to bring the conversation out of a lecture format—a powerful way to personalize and humanize the issue.

Over time, more specific police reform policies emerged and the mayor and police chief became further engaged. Eventually, per the coalition’s recommendations, the police department adopted an implicit bias training and a plan for implementing the training. The department also accepted the coalition’s recommendation for the implicit bias trainer. In tandem with these trainings, which were implemented for police officers and the department’s staff, implicit-bias community conversations were held across the city.

During this time, Council Member Applyrs and the police chief also participated in the Center for Popular Democracy’s Local Progress convening, where they had the opportunity to showcase their police reform work together. It was here they realized that they could legislate their existing police-identification policy to ensure it could be sustained through changes in the city’s administration. Applyrs seized this momentum to turn the policy into law.

The bill was relatively uncontroversial because it had no budgetary implications, although there were specific challenges Applyrs had to work out with the police department. Applyrs fought to include the language “must provide” instead of “upon request” because so few people knew they had the right to request information. This was a small but essential change to make the policy as strong as possible. The second challenge was in defining what an “encounter” was; the police department agreed to define this in partnership with community members.

The coalition is now working with the police department to roll out a community education plan. The police-identification law has also opened the door and set the tone for future police reform work by changing cultural norms and police and community interactions.

Resources

- See model a police-identification bill from Communities United for Police Reform: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B-8z1147yjwiYXZsYnNrSmwwYURHemU5Vl80WUVNaHF6dl9n/view

- See Albany’s police-identification legislation: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1gWd1l-YW3haHwyfpE3rvjUgNWRtsjSfy/view

- Read about Durham’s consent-to-search policy: https://www.southerncoalition.org/durham-adopts-written-consent-policy-for-searches/

- See the NYCLU Testimony on NYC “Right to Know” Act, which includes both police-identification and consent-to-search policies: https://www.nyclu.org/en/publications/testimony-support-right-know-act