Policy Background

Under civil forfeiture practices, law enforcement officers can seize and keep people’s personal property—for example, their homes, cars, and cash—based on the mere suspicion that the property is in any way connected to a crime. In many states, asset-forfeiture laws enable police departments to keep the majority or entirety of the seized property, creating a perverse incentive for law enforcement to steal from innocent people.[1] Asset forfeiture disproportionately impacts communities of color. For example, in 2015, the Washington Post reported that in Philadelphia, forfeiture of Black residents’ assets comprised two-thirds of all forfeiture cases, despite Blacks comprising only 44 percent of the population.[2] The ACLU of Pennsylvania also found that law enforcement took $1 million from innocent Philadelphians every year.[3] It is important to note that not all property goes through formal legal proceedings, so the full amount of property that is forfeited due to bureaucratic hurdles and lack of oversight may not be fully transparent.

One way that many local law enforcement agencies benefit directly is through their participation in the Equitable Sharing Program, a program of the Department of Justice (DOJ). The program creates a legal loophole for state and local law enforcement agencies by allowing them to prosecute some asset forfeiture cases under federal law and permitting local law enforcement agencies to keep up to 80 percent of seized property.[4] Under the Obama administration, then-Attorney General Eric Holder announced restrictions on some federal asset-forfeiture practices, but in July 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions rolled back these restrictions, reviving the Equitable Sharing Program.[5]

The Institute for Justice reports that between 2000 and 2013, annual DOJ equitable sharing payments to state and local law enforcement more than tripled—from $198 million to $643 million.[6] In that same time period, the DOJ paid state and local agencies $4.7 billion in forfeiture proceeds.[7] However, much is still unknown about the extent of the problem within states and localities; state civil forfeiture laws commonly lack transparency requirements, leaving the public with very little information about forfeiture activity and the expenditure of forfeiture proceeds.[8]

In order to prevent “policing for profit,” state and local governments should eliminate financial incentives for asset forfeiture, improve protections for residents, and mandate robust tracking and transparency. In addition, law enforcement agencies must be held to a high standard—operating under a strict burden of proof to justify any acquisition of property.

Assessing the Landscape

The following questions can help provide additional local context:

- What is the state or local asset forfeiture law?

- Does the state permit local jurisdictions to have their own forfeiture laws?

- What kind of internal police department guidelines exist?

- Has the city/county passed local legislation requiring data reporting on forfeitures and seizures?

Best Practices

Because the delegation of civil forfeiture power to local law enforcement departments is primarily based in state law, best practices are largely applicable to state law. Where local elected officials do not have authority to implement asset-forfeiture legislation, they can play an important oversight role—for example, by passing data-and-reporting legislation and requiring hearings around the data that is reported. Local elected officials can also influence the local budget process to ensure that funds from forfeitures and seizures are directed to the general fund, or better yet, toward alternatives to incarceration. Without policies that ensure seized funds are spent responsibly, they can end up directly in the pockets of law enforcement officials: In 2017, records showed that the Suffolk District Attorney’s Office in Long Island, New York, had received $550,000 in bonuses from asset-forfeiture proceeds since 2012.[9]

Asset seizure is only one form of property seizure that goes through a specific legal process. Due to a lack of resourcing, oversight, and bureaucratic hurdles, police departments keep additional property that never goes through formal legal proceedings. For example, New York City data shows that the New York Police Department claimed retaining only $11,653 and 98 motor vehicles through settlement or judgment in forfeiture actions in 2015, yet other city budget documents show that they generated over $7 million in “unclaimed cash and property sale.”[10] Local elected officials should advocate for greater reporting and transparency around all property seizures and consider resourcing systems to help people track and obtain all forms of property that have been seized.

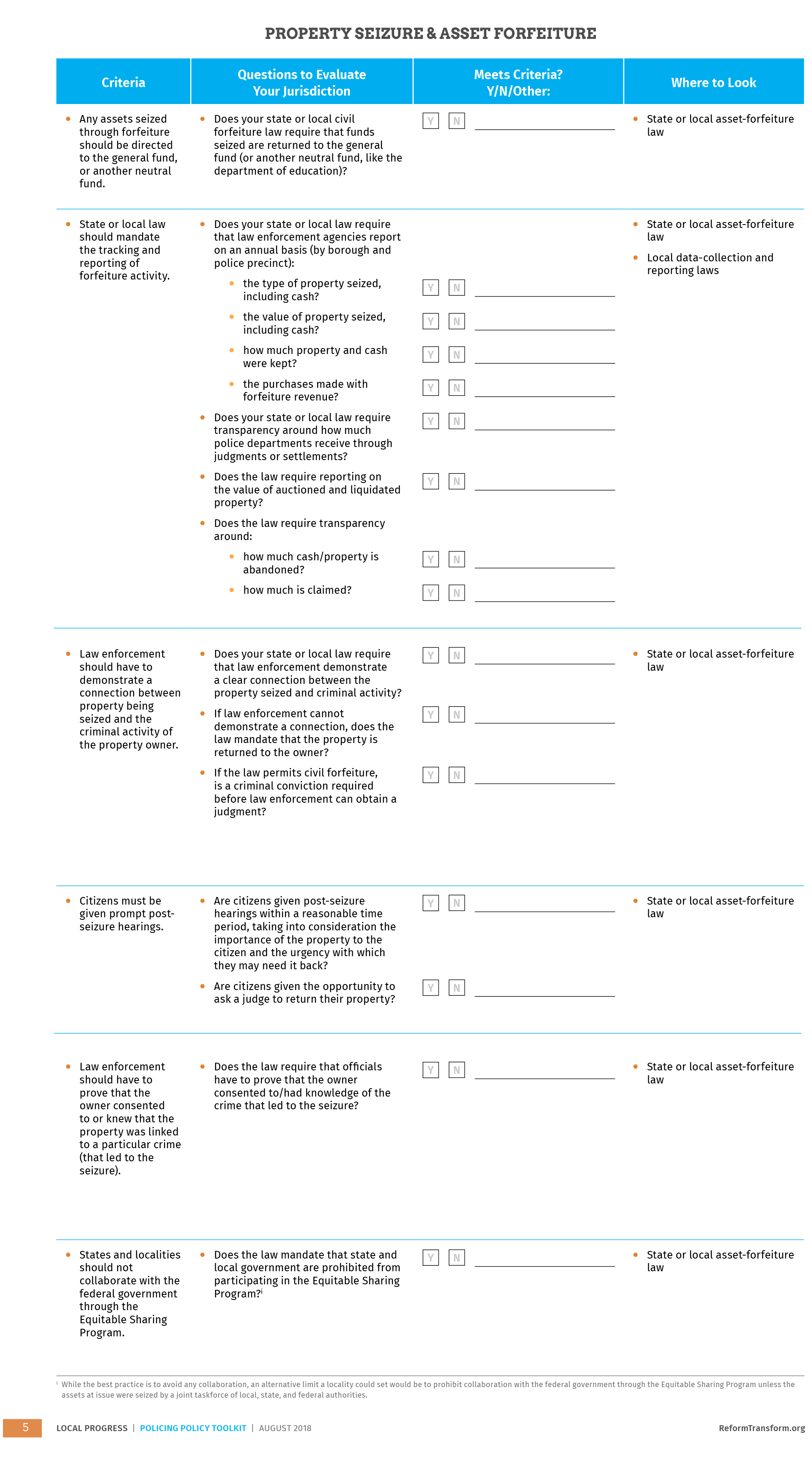

Below are criteria for a robust asset-forfeiture policies, primarily derived from recommendations from the Institute for Justice,[11] and supplemented by conversations with policy experts from the New York Civil Liberties Union and the Bronx Defenders.

Additional Criteria

- To make asset-forfeiture laws more robust, any assets seized through forfeiture should be directed to diversion or re-entry programs, or other progressive spending.

- All civilians who have had property or cash seized should have a clear way to track their property. For example, they should receive instructions about how to get their belongings back while they are being booked or immediately after arraignment.

Lessons Learned

Councilmember Charles Allen

In 2014, the Washington, D.C. Council unanimously passed the Civil Asset Forfeiture Amendment Act of 2014, granting property owners new protections, requiring greater transparency through reporting, and eventually requiring that seizure proceeds be directed to the District’s general fund rather than the police department.[12] At the time of passage, D.C. Councilmember Charles Allen was serving as Chief of Staff to former Councilmember Tommy Wells, who led the passage of bill.

Allen recalls that Wells, after becoming chair of the public safety committee, committed to tackling a number of social justice reforms, including both decriminalization of marijuana and civil asset forfeiture. In particular, the issue of civil asset forfeiture came to Wells’s attention after the Washington Post published an investigative series that exposed the extent to which civil asset forfeiture created a perverse incentive to “police for profit.”[13] The Post’s 2014 findings found that, since 2009, the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) had made more than 12,000 seizures, including $5.5 million in cash seizures and more than 1,000 cars.[14]

Councilmember Wells’s office encountered significant opposition to the reform. The former attorney general, representing the executive office of the mayor, fought the passage of the bill, as did the United States attorney’s office. The bill would have a tremendous impact on the MPD, as evidenced by the fact that the 2015 MPD budget-line item included proceeds from anticipated seizures, even though federal guidelines prohibited agencies from committing to spending in advance.[15]

To counter this opposition, Wells’s office deliberately created a broad working group to build support, comprised of various agencies and stakeholders, including the MPD, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Institute for Civil Justice. Wells depended on allied organizations who could continually push, support, and back him up throughout the fight—especially during challenging conversations with the chief of police and attorney general. They also leveraged the media to put a human face to the problem and to lift up the lived impacts of the policy, which played a key role in making a wonky policy issue more accessible to the public. The message that resonated most both in the council and in the community was framing this around fundamental issues of fairness and justice.

The successfully passed Forfeiture Amendment Act mandates annual reports to the public and to the council; the first report was submitted in June 2018, following a lengthy back-and-forth between the current attorney general and the MPD about the interpretation of the data. The 2018 report shows that from 2015 to 2017, the number of cash seizures decreased from 543 to 166 and the number of vehicle seizures decreased from 33 to 9.[16]

Resources

- See the Institute for Justice report highlighting the abuses of civil asset forfeiture: http://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/policing-for-profit-2nd-edition.pdf

- See Campaign Zero’s policy solutions on ending policing for profit: https://www.joincampaignzero.org/end-policing-for-profit

- See the ACLU of Pennsylvania’s report on civil forfeiture in Philadelphia: https://www.aclupa.org/files/3214/3326/0426/Guilty_Property_Report_-_FINAL.pdf

- See New Mexico’s civil asset forfeiture law: https://www.nmlegis.gov/Sessions/15%20Regular/final/HB0560.pdf

- See Washington, D.C.’s civil asset forfeiture law: http://lims.dccouncil.us/Download/29204/B20-0048-Engrossment.pdf