Policy Background

Over the last 30 years, at both the national and local levels, governments have dramatically increased their spending on policing and incarceration, while drastically cutting investments in basic infrastructure and slowing investments in social safety-net programs.[1] These spending patterns have continued despite the fact that studies show that providing a living wage, access to holistic health services and treatment, educational opportunities, and stable housing have far more impact on reducing crime than additional police or prisons.[2] For far too long, governments have narrowly defined and resourced public safety through the lens of greater policing and incarceration—choosing to resource punitive systems rather than supportive and nourishing ones.

Community members and advocates around the country are doing vital work to redefine and re-imagine what real safety looks like in their neighborhoods. They are making the case that increased public safety does not come from additional police officers, arrests, jails, and harsher punishments, but rather a dramatic investment in critical resources addressing the root causes of trauma, economic insecurity, housing displacement, and drug abuse.[3] Communities have highlighted alternatives such as supportive housing, community mental health clinics, jobs programs, and educational opportunities as the solutions that directly address these root causes.

Mass criminalization and incarceration are direct results of the nation’s historic systems of structural racism and discrimination, and its current manifestation is made possible through a large and complex justice system with sweeping power and huge resources.[4] In addition to outsized spending on policing and jails, local jurisdictions dedicate massive resources to related components such as probation, prosecutors, trial courts, and the bail bond industry—all of which must all be examined and addressed in policy and budgetary reform.

Most critically, any local budget campaign to divest from criminalization and invest in communities must be grounded in community demands and anchored in grassroots leadership. A robust outside strategy can provide an important lever for elected officials when engaging in budget advocacy to re-imagine public safety. Community support is essential to sustaining efforts to divest from police budgets, which are isolating, politically unpopular, and met with great resistance by well-organized institutions, such as police unions and chambers of commerce.

Assessing the Landscape

The demand for increased investments in communities requires a specific analysis based on factors such as a jurisdiction’s size, budget, and location. For example, in some rural communities in upstate New York, jails are often used as the only available mental health and substance abuse resource, creating unique challenges to demanding divestments from police or jails.[5] This type of dynamic may not be present in a larger city with existing infrastructure and resources to support non-punitive programs to better address mental health and substance abuse needs. In addition, it is important to become familiar with the jurisdiction’s police union contract, given that budget advocacy is closely tied to police union contract negotiations.

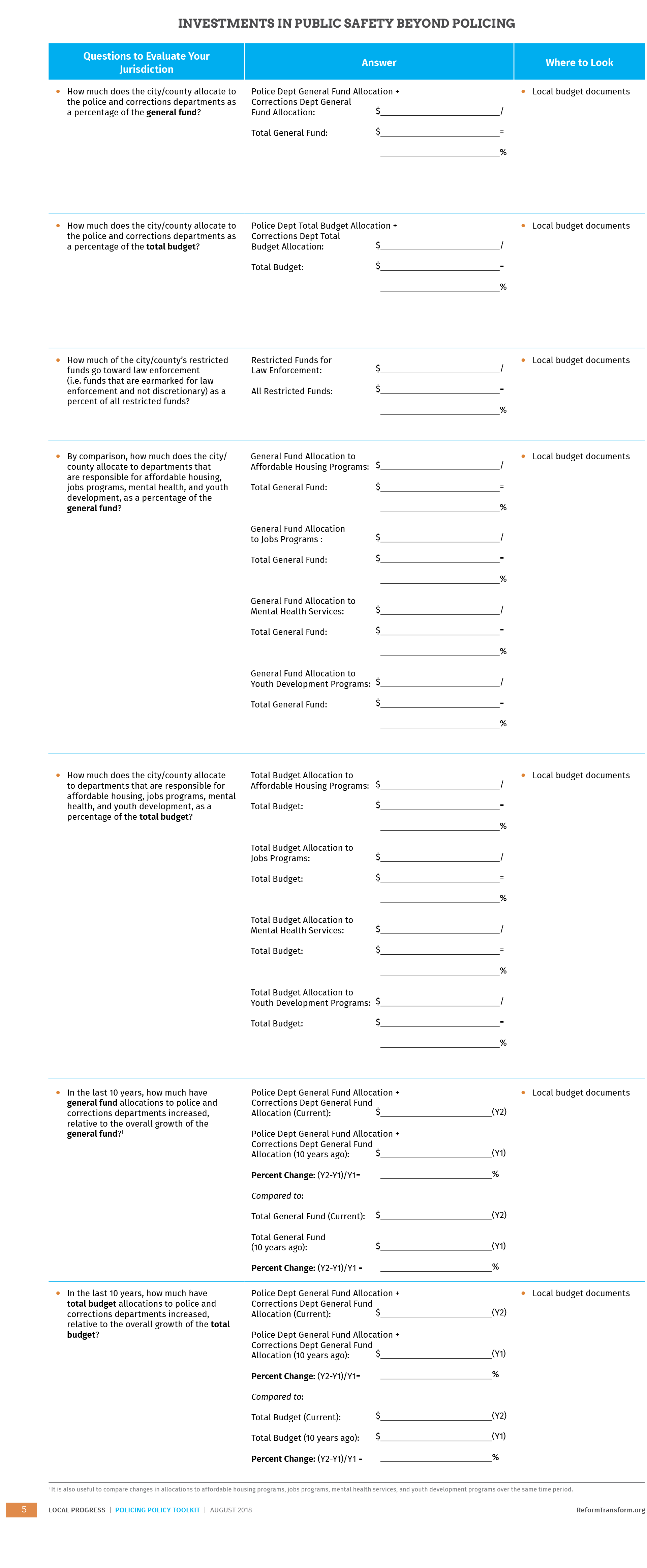

When preparing to make demands for alternative investments in public safety, local elected officials should analyze a jurisdiction’s current budget priorities, as evidenced by the relative spending dedicated to police and incarceration compared to investments in community services and resources. On its own, a local budget analysis is not a comprehensive analysis because it does not account for all state-level expenditures (for example, education is typically funded primarily at the state level), but it serves to highlight the discretionary power of cities and counties in resourcing vital community programs and services. The following questions can help to make the case that these programs and services are under-resourced when compared to police departments, jails, and other forms of criminalization.

Best Practices

Local elected officials can:

- influence the local budget process by making the case for a decreased police budget and increased investments in the departments and programs that provide mental health services, youth development, educational opportunities, job and training programs, and affordable housing;

- resist the reflexive urge to increase police department size and budget by ensuring any contemplation of additional resources to policing is a result of a clear needs-assessment, data and budgetary analysis, and full community engagement;

- demand transparency around and justification for expenditures on police and incarceration and ensure that grassroots and community groups have meaningful access to this information, enabling real-time community mobilization;

- call for an audit by the city/county auditor’s office to critically examine any reinvestment funds (i.e., toward safety beyond policing and criminalization) to ensure that spending is actually being tracked and that funds are truly being reinvested in communities, as opposed to being repackaged for purposes that do not benefit communities);

- ensure that grants for new police technology are not used to further entrench over-policing, surveillance, or criminalization;

- join the community in developing and advancing the narrative that public safety means investments in the resources and services that keep communities healthy and safe—not additional investments in police and jails;

- engage meaningfully in the contract negotiations with the relevant police union; and

- play an advocacy and oversight role to implement, collect data on, and monitor the success of programmatic investments in communities.

Additional Considerations

Additional questions include the following:

- How much does the city/county allocate to capital expenditures for the police, jails, and other forms of criminalization? (Capital budgets show how much a city/county is allocating to non-recurring infrastructure expenditures, although they may differ significantly from year to year.)

- What are the city/county’s costs per officer, per hour (looking both at salary and salary plus benefits)?

- What are the city/county’s total costs in police overtime?

- What additional income can officers earn through the department (e.g., by conducting training within the department, through overtime, paid time off, and pensions)? (While these are benefits to which all workers should be entitled and we do not advocate for cutting benefits to workers, it is important to have a clear analysis of total expenditures on police personnel. This will help to develop a full picture of a local jurisdiction’s financial liabilities.)

- How much has spending on policing and incarceration increased as a percentage of the budget in the last 10 years, relative to the growth of the overall budget (looking at both the general fund and total budget)? How does this compare to the growth of other departments?

- How much has the number of personnel grown within the police and corrections budget, compared to personal growth in other departments of interest?

- How much does the city/county spend on other forms of criminalization (e.g., criminal courts, supervision, surveillance, prosecutors, and probation)?

- Are there non-policing programs housed within other departments that actually contribute to the criminalization of communities? (For example, in some jurisdictions, the health department, which often houses critical mental health resources, may also resource carceral programs such as correctional health services or detention programs.[6])

- Is there local data demonstrating that there is no correlation between increased law enforcement budgets and decreased crime? (For reports with national statistics, see “Resources” section below.)

Lessons from the Field

John Avalos, former Supervisor

San Francisco, CA

John Avalos served on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from 2009 to 2017, during which time he leveraged his influence as city budget chair to redirect excessive spending on police overtime towards critical community-based services. In 2009, after overcoming strong opposition from the police union, Avalos and his colleagues divested $10 million from the police department and redirected that money to the city’s general fund, where it was then allocated to after-school programs, youth recreation service, youth employment programs and rental subsidies for families, among many other services at the root of public wellness and safety.

Before serving on the Board of Supervisors, Avalos worked as a community organizer. In that role, he saw firsthand the massive divestment from resources and services in communities of color and witnessed high levels of incarceration, particularly among youth. He observed heavy-handed policing practices that led to a number of violent arrests, officer-involved shootings, and the killings of several young people and adults—the majority of whom were Black and Latinx. He soon began to work on issues of police accountability with grassroots organizations like Cop Watch of the Ella Baker Center. These experiences grounded him and helped shape his priorities as he took public office.

Once in office as supervisor, Avalos saw that the city was continuing to cut critical programs like after-school and employment programs, while increasing money for the police department—particularly in police overtime pay. Part of the reason for this inflated overtime budget was a policy in the city’s charter, requiring that there must be 1,971 officers on the street. As a result of this mandate, the city put significant effort towards achieving that number, without consideration of true need or whether officers were strategically deployed. For example, instead of considering the specific needs of different precincts and communities, the department would saturate the streets with officers using overtime pay. Compounding this problem, the police academy training was failing to adequately train officers about how to prevent use of force, work with homeless people, or interact with people dealing with mental health crises.

In 2009, the first year of the Great Recession and when the city had a $500,000,000 deficit, San Francisco was once again on track to cut tens of millions of dollars in funding for community programs and to move additional money into policing and police overtime pay. As chair of the budget committee that year, Avalos launched a public fight to ensure that no particular city service would be disproportionately impacted by budget cuts, and demanded that all city departments share in the sacrifice of budget cuts. In this fight, Avalos worked closely with community groups to counter strong opposition from the police union. Thousands of people took to the streets to mobilize, including labor groups and individuals who would be directly impacted by budget cuts. Avalos strategically used media to publicize their message—not just to fight the police union, but also to advance a narrative about what public safety can look like (i.e., not just additional dollars for policing, but investments in the basic resources communities need to thrive). In the end, Avalos and the social justice community were able to reprogram over $42,000,000 in general-fund dollars to safety-net and violence-prevention services. This figure allowed for redundancies and inefficiencies in public safety departments to be greatly reduced without eliminating any police officers or other public safety staff.

Chicago, IL

Alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa

In Chicago, the No Cop Academy campaign is an effort led by community organizations across the city to stop the construction of a $95 million cop academy (to be used for police training), and instead invest those resources in youth and communities.[7] Alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa has been one of the only members of council to oppose the mayor by voting against the project, choosing to stand in solidarity with communities despite the political unpopularity of his stance.

In the media, the dominant narrative about crime in Chicago has been that the city should address crime by increasing the number of police and funding for the police department. Organizers are working to reframe the definition of public safety, calling for investments in job programs, mental health resources, and education. Many of these organizations are Black- and youth-led organizations, like BYP100 and Assata’s Daughters, who are advancing a bold and transformational vision of community safety. As an elected official, Ramirez-Rosa has committed to following the lead of these community leaders, and to opening up space for them at the policymaking table.

Alderman Ramirez-Rosa first engaged in this fight after learning about the community response to the mayor’s announcement about the new cop academy. He came across the No Cop Academy’s campaign’s website and reached out to the organizers to arrange a meeting. The organizers shared their priorities for the $95 million—i.e. funding for youth and communities, not for new funding for the police—and Alderman Ramirez-Rosa committed to being their champion on the council.

However, Ramirez-Rosa quickly realized how challenging it would be to recruit his colleagues on the council to vote to shift resources from policing to other programs. Although he had secured commitments from six colleagues to vote against using tax increment financing (TIF) to purchase the land for the academy, all six voted yes at the last minute. In preparation for the second vote, which would approve funding for the academy, organizers conducted targeted canvassing and outreach to gain support of additional aldermen to vote no. Despite their attempts, the mayor successfully stymied these efforts: only two additional aldermen voted against the funding. A third of the funding for the project is now allocated, and the council is currently waiting to hear from the mayor about where the additional funding will come from.

Despite the roadblocks, one promising outcome of the efforts to-date is that it has become clear that many residents agree that public safety dollars should go toward communities and neighborhoods instead of police. Eighty-eight percent of voters surveyed in Chicago’s Ward 37 sided with organizers, agreeing that money would be better invested in communities. In the Fourth Congressional District, about two-thirds of voters agree that to improve public safety, the city should invest in funding education and after-school education, jobs programs, and mental health services.

Resources

- See a report by the Open Philanthropy Institute, “The impact of incarceration on crime,” that shows incarceration has little to no impact on crime: https://www.openphilanthropy.org/files/Focus_Areas/Criminal_Justice_Reform/The_impacts_of_incarceration_on_crime_10.pdf

- See a report by the Justice Policy Institute, “Rethinking the Blues: How We Police in the U.S. and at What Cost,” that shows that more police do not lead to more public safety: http://www.justicepolicy.org/uploads/justicepolicy/documents/rethinkingtheblues_final.pdf

- See the “Freedom to Thrive” report by the Law for Black Lives, BYP100, and the Center for Popular Democracy: http://populardemocracy.org/news/publications/freedom-thrive-reimagining-safety-security-our-communities

- See NYC’s Safety Beyond Policing campaign: http://www.safetybeyondpolicing.com/

- Read about the Freedom Cities movement: http://ellabakercenter.org/blog/2017/07/freedom, http://freedomcities.org/

- Read about the #NoCopAcademy campaign in Chicago: https://nocopacademy.com/about/

- Read about the Anti Police-Terror Project’s “Defund OPD” Campaign in Oakland: https://www.defundopd.org/opd-facts-and-figures