Policy Background

Across the nation, police departments have become heavily armed and increasingly militarized, in large part due to federal programs that have equipped state and local law enforcement agencies with military-grade equipment and weapons, all with very little oversight.[1] In 1990, Congress enacted the National Defense Authorization Act, which authorized the Defense Department to transfer surplus military-grade weapons and equipment to local law enforcement agencies at little or no cost.[2] Examples of the types of equipment and weapons received by local police departments under this program (known as the 1033 program) include: aircrafts, armored vehicles, body armor, grenade launchers, and assault rifles.[3] Local police departments have received transfers ranging from less than $200 to multi-million dollar transfers.[4] While President Obama put restrictions on federal transfers of military equipment in 2015, in August 2017, President Trump, without public input, issued an executive order which reinstates the transfer of military-grade tactical equipment and surveillance technologies to local police departments.[5]

As a result of these programs, police departments have become increasingly militarized in their tactics, which include aggressive and often violent SWAT deployments for low-level investigations.[6] In a 2014 report, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) found that the majority of SWAT deployments (79 percent) were to execute search warrants for low-level drug investigations, and deployments for hostage or barricade situations occurred in only a small number of incidents.[7] The study also found that, based on recorded data, the use of paramilitary weapons and tactics primarily impacted people of color. When used in drug searches, the primary targets of paramilitary tactics were people of color, whereas when used in hostage or barricade scenarios, the primary targets were white.[8]

However, militarized tactics are not exclusive to SWAT deployment, and can show up in any type of police-community interaction. During heightened moments of resistance and mobilization in the streets, police have used militarized tactics to quell protest. For example, during the Ferguson uprising, law enforcement used snipers, armored vehicles, and tear gas on protesters.[9] In neighboring St. Louis, officers deployed tear gas without warning and kettled demonstrators who protested the acquittal of a white officer who fatally shot Anthony Lamar Smith, a Black man.[10]

Assessing the Landscape

Before assessing the strength of a local jurisdiction’s policy, local elected officials should answer the following questions to estimate the amount of military equipment received by local law enforcement and the locality’s policies around deployment of SWAT teams.

- Does your city or county participate in the 1033 program? (To view 1033 program data, see: http://www.dla.mil/DispositionServices/FOIA/EFOIALibrary.aspx)

- Does your city or county buy weapons using money obtained through the Department of Justice’s Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) program? (See http://www.ncjp.org/state-agencies for state profiles and a breakdown of local grants.)

- Does your city or county use funding from the Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Security Grant Program to purchase military-style weapons? (See https://www.homelandsecuritygrants.info/GrantDetails.aspx?gid=17162, “Award Details” for more information about award allocations, although additional research may be required to determine use of grants.)

- Does the local law enforcement agency use civil asset-forfeiture funds, private donations, or other off-the-books funding to purchase military equipment?

- Does the local law enforcement agency have a local policy around internal SWAT deployment standards? (To answer this question, a Freedom of Information Act request may be required. To see a sample public records request, see Appendix A of the ACLU’s report, “War Comes Home”)

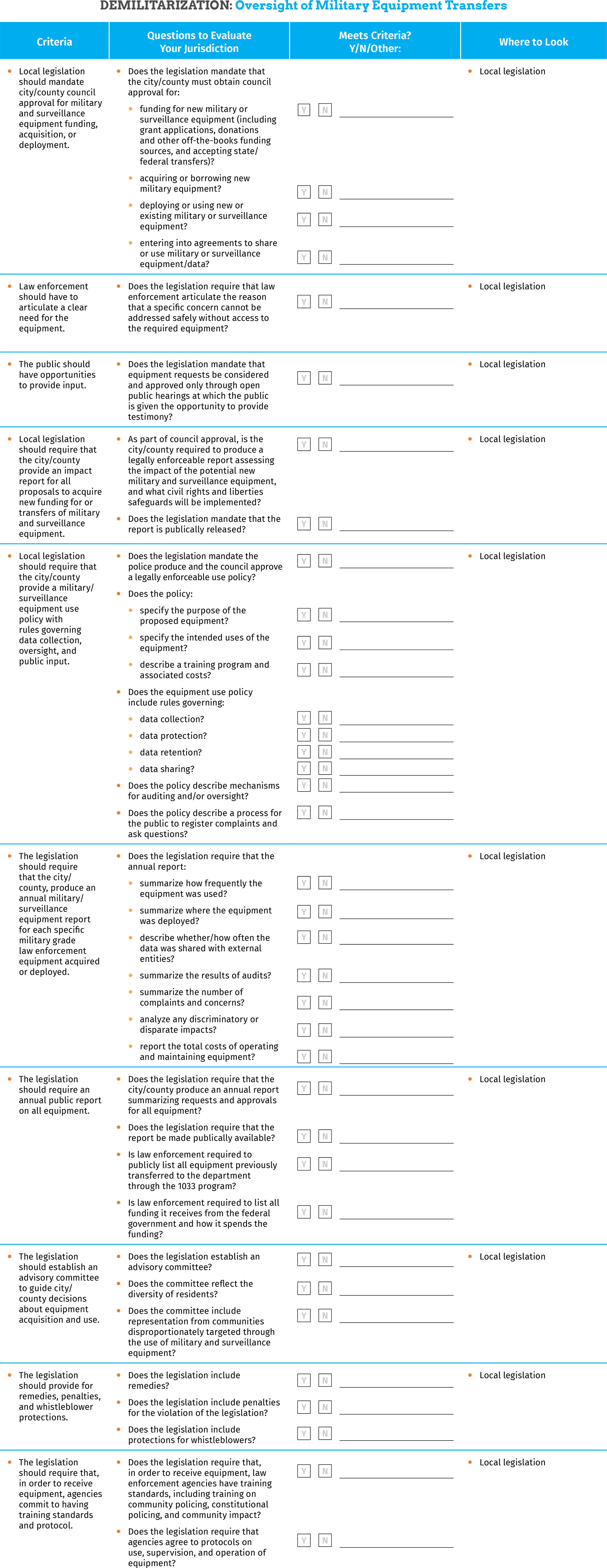

Best Practices: Oversight of Military Equipment Transfers

Local elected officials can address the over-militarization of local law enforcement by enacting legislation that gives local elected officials greater oversight and authority over the transfer of military-grade equipment to local law enforcement agencies.[11] A gold standard policy would ban all transfers of military equipment to local law enforcement agencies; however, an acceptable compromise in some jurisdictions might allow for the transfer of non-military grade equipment, such as desks and computers.[12] Regardless of the policy on the type of equipment that may be transferred, local elected officials can establish robust processes to ensure oversight, accountability, and community input.

The below criteria are from the ACLU’s model bill, “An Act to Promote Transparency, the Public’s Welfare, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties In All Decisions Regarding The Funding, Acquisition, and Deployment of Military and Surveillance Equipment,”[13] and supplemented with conversations with policy experts from the ACLU and One Thousand Arms.

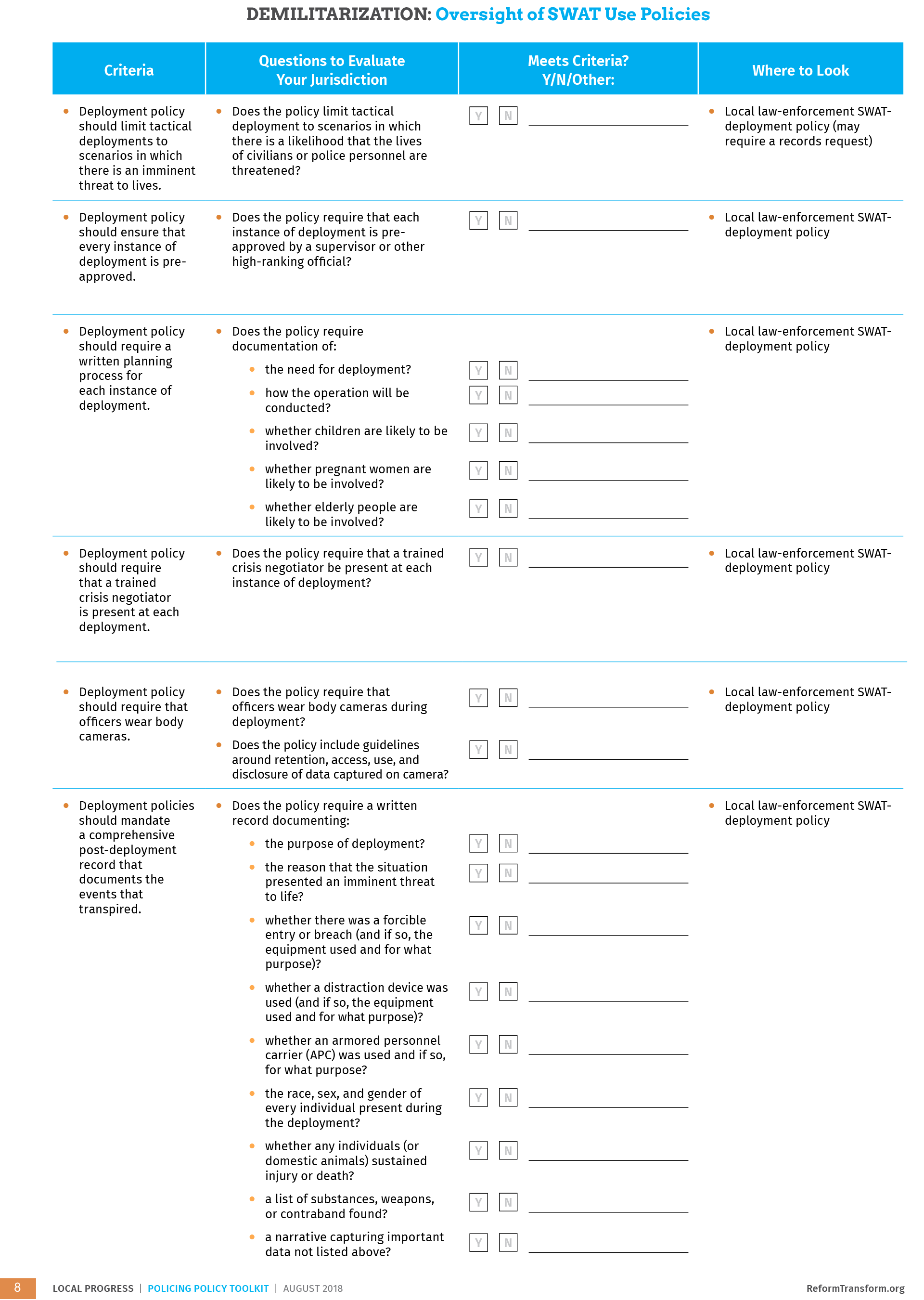

Best Practices: Oversight of SWAT Use Policies

Local elected officials can also play an oversight and advocacy role by pushing police departments to adopt strong local policies around SWAT deployment. The below criteria are from the ACLU’s recommendations to city and county governments and law enforcement agencies around SWAT deployment, from the report “War Comes Home.”[14]

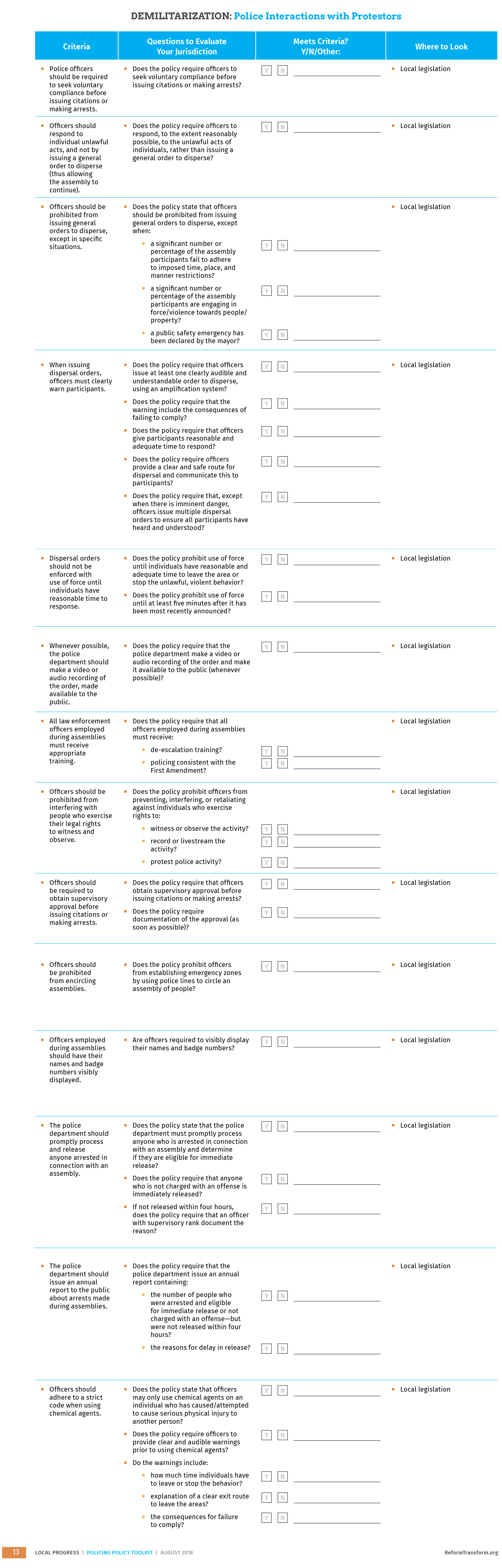

Best Practices: Police Interactions with Protestors

Elected officials can pass local legislation to oversee the deployment and practices of police during First Amendment-protected activities, such as protest. The following criteria was derived from Board Bill 134 in St. Louis, MO[15] and informed by conversations with policy experts from the ACLU.

Lessons from the Field

Seattle, WA

Councilmember Lisa Herbold

In 2017, Seattle City Councilmember Lisa Herbold championed and passed a demilitarization policy through city budget legislation, which prohibits the police department from receiving military equipment through the federal 1033 program. Furthermore, the council required the police department to return the majority of equipment received through the program, with the exception of some coveralls, gloves, and a metal utility cabinet.[16]

Councilmember Herbold had learned about what councilmembers could do through her participation in the Center for Democracy’s Local Progress network. While her bill was not controversial, there were several factors that contributed to the smooth passage of this legislation. When Seattle’s then-mayor became embroiled in a scandal and subsequently resigned, there was uncertainty about whether or not there would be a new police chief—and as a result, whether or not current police department policies would change. Herbold was able to leverage the mayoral turnover to argue that the city should codify the policy through legislation. Furthermore, the police chief had already voluntarily ended the department’s participation in the 1033 program through departmental policy, beginning in 2015. Herbold also made the case that, because the 1033 program would likely become more robust and attractive to local law enforcement under Attorney General Sessions, the passage of legislation would ensure that the policy would be sustained through changing political tides. And as budget chair that year, Herbold was in an influential position to champion this reform.

During the budget negotiation process, Councilmember Herbold made sure to connect with community groups and advocates to understand their perspective on this issue, including the ACLU and the Community Police Commission. She experienced no opposition from law enforcement or the police union, which ensured passage of the legislation.

According to Herbold, cities should “ensure that the legislative body’s intention that we demilitarize our police force is actualized and real, and not left up to the police department to make that determination. A police department that is not militarized is a force that has higher potential and stronger chance to build a better relationship with the broader community.”

St. Louis, MO

Alderwoman Megan Green

In 2017, St. Louis Alderwoman Megan Green introduced Board Bill 134 to protect the First Amendment rights of protesters.[17] The bill would “repeal the city’s constitutionally vague ordinance regarding ‘unlawful assembly’” and establish protocols to protect the rights of those “observing, recording or participating in protest activity.”

Alderwoman Green’s commitment to protecting the rights of protesters has been informed by personal experience. In 2014, the day after she was elected to office, an unarmed Black teenage boy, VonDerrit Myers, was killed by the police in a neighboring ward. One month later, a grand jury decided not to indict Darren Wilson, the white officer who killed Michael Brown in Ferguson. These events—the latest in a long history of brutality at the hands of the police—fueled a large protest in a neighboring ward, which she attended.

During the protest, a group of about 1,000 activists marched peacefully and blocked traffic on a highway before returning to the city’s business district. Once in the business district, the activists witnessed, and successfully stopped, a few isolated acts of vandalism by several young people who had not been participants in the action. Nearly an hour after this transpired, the police drove through the district and tear gassed the protesters in an MRAP (a military vehicle), shooting rubber bullets into the crowd without any warning.

Alderwoman Green took refuge in a nearby coffee shop, along with other protesters and legal observers. At that point, police formed a line that prevented protesters from getting to their cars and threw another can of teargas outside, forcing some protesters to retreat into the shop and bring the fumes inside with them. In all, Alderwoman Green was tear gassed on three separate occasions in the same night–without any warning or notice.

After these events, the owner of the coffee shop and several plaintiffs sued the city on the grounds that its unlawful assembly ordinance is vague and unclear, and that no notice was given before chemical agents were used. A federal judge determined that the police needed to issue fair warnings before dispersing chemicals.

However, in September 2017, protests arose again when Jason Stockley, another white St. Louis police officer, was acquitted after he shot and killed Anthony Smith, a Black man. Police officers aggressively used chemical agents to disperse protests. Once again, activists prevailed when a federal judge ruled that the St. Louis police cannot prevent non-violent demonstrations or use chemical weapons on peaceful protesters. Following this second win in court, activists determined that the injunction should be codified into policy. Alderwoman Green worked with the ACLU of Missouri to draft Board Bill 134 and today is still fighting to pass it through the Board of Aldermen.

Resources

- See the ACLU’s model legislation, “An Act To Promote Transparency, the Public’s Welfare, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties In All Decisions Regarding The Funding, Acquisition, and Deployment of Military and Surveillance Equipment”: https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/aclu_ccopsm_surveillance_military_equipment_model_bill_september_2017.pdf

- See Board Bill 134 by Ald. Megan Green in St. Louis concerning the rights of protesters: https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/city-laws/board-bills/boardbill.cfm?bbDetail=true&BBID=10899

- See Seattle’s ordinance to decrease the militarization of police activities: http://seattle.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=5695993&GUID=C5174925-176C-468C-9E00-2A471212AAE8

- See data on transfers made through the 1033 Program: http://www.dla.mil/DispositionServices/FOIA/EFOIALibrary.aspx

- See data on the Department of Justice’s Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) program: http://www.ncjp.org/state-agencies

- Read about the Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Security Grant Program to purchase military-style weapons: https://www.homelandsecuritygrants.info/GrantDetails.aspx?gid=17162

- See the ACLU’s 2014 Report, “War Comes Home: The Excessive Militarization of American Policing”: https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/jus14-warcomeshome-text-rel1.pdf

- See Kara Danksy’s article, “Local Democratic Oversight of Police Militarization”: http://harvardlpr.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/10.1_5_Dansky.pdf

- See “Militarization and police violence: The case of the 1033 program,” exploring the relationship between equipment transfers and officer violence: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2053168017712885

- Read about the Alameda County Board of Supervisors’ vote to end Urban Shield after 2018, the world’s largest militarized SWAT training and weapons expo: http://stopurbanshield.org/in-historic-vote-alameda-county-board-of-supervisors-votes-to-end-highly-militarized-urban-shield-swat-program-after-2018/